At the end of the year 1772, three Bretons were part of a magnificent cavalcade that made its way towards the barbican* of the Qila-e-Mualla of Delhi, preparing to meet the newly returned Emperor Shah Alam in grand durbar. In the middle of a cortege of splendidly dressed cavalry, grenadiers, guards, and Mughal noblemen swayed five richly caparisoned elephants. On one of the elephants sat the fifty-year-old Persian commander, Mirza Najaf Khan, recently promoted to Mir Bakshi of the Mughal empire and next to him on his elephant sat an awestruck René Madec in his best regimental uniform, quite overcome. ‘I may declare without exaggeration that I entered the capital of India more like a monarch than as a mere individual and subject of the emperor’ admitted the Breton proudly. The once scrappy, penniless youth from Brittany now found himself a man of substance, alighting from the elephant in front of the naubat khana of the Qila of Delhi, where the musicians immediately burst into triumphant, acclamatory music. Madec made his way slowly down the marble paths, shadowed by the memory of long-dead emperors and their magnificent daughters. Next to the marbled fountains, courtiers flew kites nonchalantly, impervious to the grandeur of the moment. Madec stopped in front of the diwan-e-khas, where there was a press of supplicants waiting to see the emperor. Among them was his compatriot and fellow Breton, Daniel du Jarday, dressed as a Mughal and passably incognito. Alongside Madec was another Breton officer, de Kerscao, a nobleman from the French colony of Reunion Island.

At last the emperor appeared, sitting upon a simple wooden throne borne upon a palanquin and preceded by stout guards striking the ground with their sticks, and loudly proclaiming the glory of the emperor. After Madec had presented his nazr (seven silver coins) to Shah Alam, he was given a khillat which he was made to wear in the emperor’s presence. Finally, the emperor removed his own sword from his side and presented it to the Frenchman. ‘I could barely believe this was not a dream’, wrote Madec, very moved by the emperor’s gesture. Madec was also given a respectable brace of titles,* enough to call himself a nawab, or nabob, henceforth.

Madec had had a rambunctious career in Hindustan ever since Shuja had been forced to let him go after the Battle of Buxar.†Along with his party of 400 trained soldiers, he had fought for the Rohillas, and then the Jats, and had established a reputation for valour and military skill. He also got married to the young Marie-Anne Barbette‡ in a ceremony that lasted several days, during which 10,000 people were fed every day. Despite the truly Hindustani opulence of the wedding, Madec seems to have been disappointed by his young bride’s lack of charms, for he wrote rather regretfully that ‘the Catholics in this country follow the traditions of the locals. One may only see one’s wife after the marriage ceremony…and one may thus discover a Lea instead of a Rachel.’ A portrait of Marie-Anne Barbette does indeed depict a snub-nosed, pleasantly chubby woman with an unremarkable face, but Madec would console himself by taking a second, presumably comelier, Muslim wife.

Madec was most pleasantly established as a profitable mercenary when he received an unexpected summons from the Governor of the French trading post at Chandernagore. Governor Jean-Baptiste Chevalier has been described by a French historian as an ‘ardent patriot’ and a man with ‘grand dreams’ who used his abundant energy to plague the French ministry with a flood of letters, offering inventive ways through which to regain French influence in India.

Once Shah Alam had been reinstated in Delhi, Chevalier was electrified by the possibility of gathering a substantial force around the emperor, one that could be used to attack the British in their stronghold in Bengal. To this aim, Chevalier had initially pleaded with his government in Versailles to send 4,000 troops who would be placed under Madec to help the Mughal emperor regain Bengal. But the French government did not want to be seen to be provoking the English and so instead Chevalier decided to gather as many independent French partisans to the emperor’s cause as possible, in the hope that they might counter English interests. Indeed, French policy at this point was to consistently oppose the English in the three main theatres of conflict—North America, the Caribbean and, increasingly, Asia. Agents were sent from France in the guise of civilians to gather intelligence in Indian states deemed likely to oppose the English, such as Mysore, Hyderabad, Lucknow, and the area around Delhi. And if French efforts to thwart the English had now gathered momentum, then the English themselves were facing a potentially disastrous situation, both in Bengal and in America. In Bengal, a 1773 Select Committee* found that an astounding 2 million pounds had been removed from the Bengal treasury and distributed as ‘presents’, almost all to local EIC employees. And while these obscene sums of money were being confiscated by employees, Bengal itself convulsed in the throes of a dreadful famine, exacerbated by the actions of the Company. When questioned, Clive would respond, with the chilling sangfroid of a true sociopath, that his allegiance was to the shareholders of the EIC, not the people of Bengal. But the 3 million deaths caused by the famine annihilated the productivity of Bengal, bringing the EIC to the edge of bankruptcy. In response, the government in London decided to raise taxes in their colonies in North America, by passing the Tea Act in 1773,† to fund the bail out of the EIC in India. The resulting rage of the American settlers would lead to the Boston Tea Party and, within a few years, to the American War of Independence. The EIC would pay its debt for Bengali blood on American soil.

Meanwhile, in India, Chevalier was intent on securing the support of René Madec. ‘What could possibly interest you, sir,’ harangued Chevalier, ‘other than gaining a good name among your compatriots by attaching yourself firmly to France’s cause?’ But there was much else that interested the pragmatic, avaricious Breton, namely money. ‘I fail to see,’ protested Madec, ‘how I may be of service to my nation. I simply wish to return to Europe to enjoy the fruits of my actions.’ ‘You are brave,’ encouraged Chevalier undeterred, ignoring his protests.

‘The princes of Hindustan want you by their side. In your position, you could bring about a revolution capable of shaking our nation out of the state of torpor where it finds itself today in India.’ By now, with the Marathas having aligned themselves with the Mughal cause, Chevalier was conjuring a glorious vision in which France played a leading role against the English, just as she was beginning to do in the American colonies, and reconquered Bengal for the emperor. Finally, giving in to the flattery as well as to some subtle blackmail,* Madec agreed. ‘I will sacrifice my desire to return to France to my great zeal to serve my King. I give you my word that if France decides to march to Bengal, I will join the cause with ten thousand men, at my expense.’ And so it was that this one-time ship’s apprentice† found himself in the Mughal capital wearing a splendid turban and tunic, appointed a sapt-hazari,‡ and preceded by a troupe of musicians permitted to lustily announce his arrival (image 13).

For a short while in Delhi, René Madec found himself an incongruous courtier at the court of the Mughal emperor. He let his beard grow out, like the other Mughal lords, and took up the suitably aristocratic pastimes of polo and archery. The coat of his favourite horse was festooned with floral designs drawn in henna, and he vaulted with his usual enthusiasm into all the courtly activities—camel, ram, and antelope fights, fireworks, and even poetry competitions in the emperor’s mushairas§. Madec also had intimate tête-à-têtes with the Mughal emperor who, encouraged by letters from the dogged Chevalier in Chandernagore, ‘exhibited a strong desire to begin a correspondence with the French king, to obtain his help so as to enable him to earn the respect of his own subjects.’

But in these churning days in Delhi where every warlord and raja was setting himself up as an independent force, the emperor was quite besieged. He had initially appointed the talented general Najaf Khan to regain the territories around Delhi that had been seized by the Rohillas and Jats during his long absence from the capital.

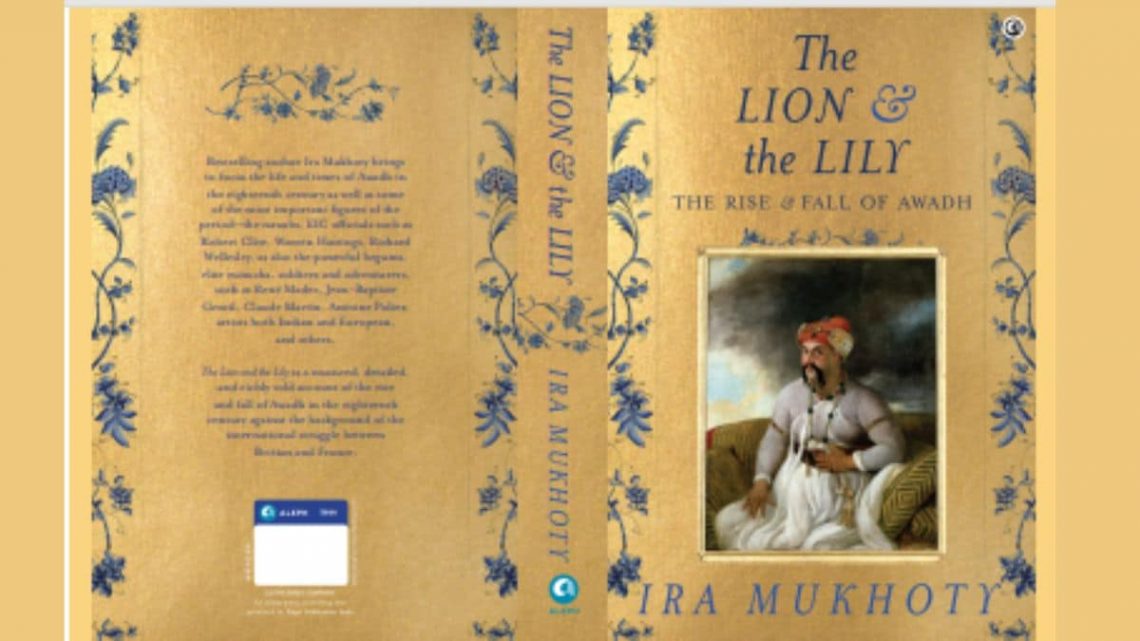

(Ira Mukhtoy is the author of Akbar: The Great Mughal, Song of Draupadi: A Novel, Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire, and Heroines: Powerful Indian Women in Myth and History. Living in one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, she developed an interest in the evolution of mythology and history, and the erasure of women and other marginal voices from these histories. She writes rigorously researched narrative histories that are accessible to the lay reader.)

Link to article –